Chronobiology and Nutrition: Timing Your Meals for Optimal Health Benefits

Discover how chrononutrition—aligning meal timing with your circadian rhythm—optimizes hormonal balance, metabolism, and overall health. Key strategies include time-restricted eating (TRE), prioritizing larger meals earlier in the day, and avoiding late-night eating to enhance insulin sensitivity, fat burning, and cellular repair. Front-load calories with a hearty breakfast, aim for a 12-hour fasting window, and sync meals with natural energy peaks to support weight loss, athletic performance, and cognitive function. Tailor plans for shift workers, women, and older adults, leveraging consistent meal times and overnight fasting to reduce risks of diabetes, heart disease, and metabolic disorders. Embrace chronobiology to improve sleep quality, stabilize hunger hormones, and boost metabolic flexibility. Start with small steps like finishing dinner earlier or adopting a 12-hour fast to align eating patterns with your body’s internal clock for lasting health benefits.

DIET & NUTRITION

Alex Tan

4/17/20259 min read

Chronobiology and Nutrition: Timing Your Meals for Optimal Hormonal Balance

Introduction: Why When You Eat Matters

For years, nutrition advice has focused on what to eat—fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains. But a new field called chrononutrition is shifting the spotlight to when you eat. Chrononutrition explores how the timing of meals interacts with your body’s internal clock, or circadian rhythm, to influence metabolism, hormone production, cellular repair, and even your risk for chronic disease124.

This article delves into the science of chronobiology and nutrition, explains why meal timing matters, and provides practical strategies for aligning your eating schedule with your body’s natural rhythms—whether your goal is weight management, athletic performance, or simply feeling your best.

Understanding Chronobiology: The Body’s Internal Clock

The Circadian Rhythm and Metabolic Health

Every cell in your body follows a 24-hour cycle called the circadian rhythm. This rhythm is orchestrated by a “master clock” in your brain—the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—which is set by exposure to light and darkness1020. The SCN coordinates “peripheral clocks” in organs like your liver, pancreas, gut, and muscles, ensuring that vital processes like hormone secretion, digestion, and cellular repair occur at the right times.

Morning: Cortisol and insulin sensitivity peak, priming your body for activity and efficient carbohydrate metabolism8.

Afternoon: Physical performance, muscle strength, and coordination are at their highest.

Evening: Melatonin rises, preparing your body for sleep. Digestion and metabolism slow down.

Chronodisruption: What Happens When Timing Goes Wrong

Modern life—late-night eating, shift work, jet lag, and artificial lighting—can disrupt circadian rhythms, a phenomenon known as chronodisruption. This misalignment has been linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even certain cancers121020.

For example, studies show that people who eat most of their calories late in the day or skip breakfast are more likely to gain weight and develop metabolic syndrome, regardless of total calorie intake820.

The Science of Chrononutrition: Key Concepts

1. Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) and Intermittent Fasting

Time-restricted eating (TRE) is a form of intermittent fasting that limits food intake to a specific window each day—often 8 to 12 hours—while fasting the rest of the time2411. Unlike traditional calorie restriction, TRE focuses on when you eat, not how much.

Scientific Insights

Metabolic Benefits: TRE has been shown to promote weight loss, reduce waist circumference, and lower blood pressure—even without deliberate calorie reduction2411.

Insulin Sensitivity: Early TRE (eating between 6 a.m. and 3 p.m.) improves insulin sensitivity and glucose control compared to eating later in the day813.

Liver Health: TRE may be especially beneficial for managing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) due to its effects on body weight and fat loss24.

Adherence: In a pilot study, adults with overweight who reduced their eating window from 16 to 12 hours experienced weight loss and improved blood pressure, with moderate adherence rates4.

Practical Example

A typical TRE schedule might involve eating breakfast at 8 a.m., lunch at 1 p.m., dinner at 6 p.m., and fasting from 7 p.m. until breakfast the next day. This 13-hour fast allows the body to switch from burning glucose to burning stored fat, supporting metabolic flexibility.

2. Synchronizing Nutrition with Circadian Rhythms

Eating in sync with your circadian rhythm means:

Consuming most calories earlier in the day.

Avoiding large meals late at night.

Why it matters: Studies show that identical meals eaten at different times of day produce different metabolic responses. For example, glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity are highest in the morning and lowest at night813. Eating late at night, especially during periods of high melatonin, impairs glucose tolerance and increases fat storage8.

3. Metabolic Flexibility and Hormonal Balance

Metabolic flexibility is your body’s ability to switch efficiently between burning carbohydrates and fats for fuel. Chrononutrition supports metabolic flexibility by encouraging overnight fasting and aligning meals with periods of peak insulin sensitivity413.

Hormonal effects: Key hormones like insulin, ghrelin, leptin, and melatonin all follow circadian patterns and respond to meal timing3789.

Insulin: Peaks in the morning, declines in the evening. Late meals lead to higher blood sugar and more fat storage813.

Ghrelin: The “hunger hormone” rises before meals and falls after eating. Regular meal timing helps regulate ghrelin and appetite39.

Leptin: The “satiety hormone” signals fullness. Chronodisruption can impair leptin rhythms, making it harder to feel satisfied39.

Melatonin: Rises in the evening to prepare for sleep. Eating late, especially high-carb meals, can suppress melatonin and disrupt sleep and cellular repair816.

Meal Timing for Different Health Goals

1. Weight Management

The Case for a Big Breakfast

Front-loading calories—eating a substantial breakfast and lighter dinner—can aid weight loss and improve metabolic health. In a randomized trial, participants who ate a high-calorie breakfast and low-calorie dinner lost more weight and had greater reductions in waist circumference compared to those with the opposite pattern1317.

Why?

Insulin sensitivity is highest in the morning, so your body processes carbohydrates more efficiently.

A hearty breakfast reduces hunger hormones (ghrelin) and curbs evening cravings378.

Avoiding Late-Night Eating

Eating late at night is associated with higher blood sugar, increased fat storage, and impaired lipid metabolism. Night shift workers and late eaters are at greater risk for obesity and metabolic syndrome6813.

Practical Tips:

Finish your last meal at least 2-3 hours before bedtime.

If you must eat late, choose light, protein-rich foods rather than heavy carbs or fats.

Real-World Example

A busy professional who often works late might prepare a balanced dinner in advance and eat it at the office before heading home, avoiding the temptation of late-night snacking.

2. Athletic Performance

Pre-Workout Nutrition

Eating a balanced meal with complex carbohydrates and protein 2–3 hours before exercise provides energy and supports muscle function. For early-morning workouts, a small snack (like a banana or yogurt) can be sufficient13.

Post-Workout Recovery

Consuming protein and carbohydrates within 30–60 minutes after exercise maximizes muscle repair and glycogen replenishment. Aligning workouts and meals with your natural energy peaks (afternoon or early evening) can further enhance performance13.

Muscle Mass and Function

A recent study in older adults found that a longer eating window and a later last intake time were associated with greater muscle mass and leg power, while an earlier intake time was linked to higher grip strength5. Even protein distribution matters: spreading protein intake evenly across breakfast, lunch, and dinner is better for muscle health than consuming most protein at dinner5.

3. Cognitive Function

Breakfast for Brain Power

Skipping breakfast is linked to reduced memory, slower reaction times, and poorer academic performance. A balanced breakfast stabilizes blood sugar and supports sustained mental focus817.

Stable Meal Patterns

Irregular eating patterns—like skipping meals or eating at random times—can disrupt circadian rhythms and impair cognitive performance. Eating at consistent times each day helps maintain mental clarity and mood1817.

Practical Example

A student who eats breakfast at the same time each day and avoids late-night snacking is likely to experience better concentration, memory, and mood.

Chrononutrition and Hormonal Regulation: The Science in Detail

Ghrelin, Leptin, and Appetite Control

Ghrelin, known as the “hunger hormone,” rises before meals and drops after eating. Regular meal timing helps regulate the pre-meal surge of ghrelin, reducing the risk of overeating3914. Leptin, on the other hand, signals fullness and is influenced by meal timing and sleep patterns914.

Scientific Example:

In controlled studies, people who slept and ate earlier had higher overnight leptin concentrations and greater GLP-1 (a satiety hormone) responses to meals, leading to better appetite control and reduced food intake914.

Insulin, Melatonin, and Glucose Control

Insulin sensitivity is highest in the morning and lowest at night. Eating late, especially during periods of high melatonin (the hormone that prepares the body for sleep), impairs glucose tolerance and increases the risk of diabetes813.

Genetic Factors:

Some people carry genetic variants (like the G allele in the MTNR1B gene) that make them more sensitive to the negative effects of late-night eating on glucose control8.

Chrononutrition for Special Populations

Shift Workers

Shift work disrupts circadian rhythms and increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease620. However, strategic meal timing can help:

Anchor Meal: Eat your largest meal at the start of your “day,” even if it’s at night6.

Consistent Eating Window: Keep your eating window the same length each day, even if the hours shift.

Light Exposure: Use bright light during your shift and blackout curtains during sleep to help reset your internal clock.

Women’s Health: Menstrual Cycle, Pregnancy, and Menopause

Menstrual Cycle: Hormonal fluctuations affect appetite and metabolism. Synchronizing meals with these shifts may help manage cravings and energy levels19.

Pregnancy: Irregular mealtimes and late-night eating may contribute to gestational diabetes and excessive weight gain. Structured meal timing that aligns with circadian rhythms supports maternal and fetal health19.

Menopause: Declining estrogen disrupts circadian rhythms, leading to sleep disturbances and insulin resistance. Time-restricted eating may help mitigate these effects19.

Older Adults

Chrononutrition is especially important for older adults, who are at risk for muscle loss (sarcopenia) and metabolic decline. A longer eating window and even protein distribution support muscle mass and function, while an earlier first meal is linked to better grip strength5.

Children and Adolescents

Regular breakfast consumption is crucial for preventing obesity and supporting healthy growth. Skipping breakfast or eating late is linked to higher risk of metabolic abnormalities in youth17.

Personalized Chrononutrition: Chronotype and Genetic Differences

Chronotype: Larks vs. Owls

People have different “chronotypes”—natural preferences for waking early (“larks”) or staying up late (“owls”). Chronotype influences dietary habits, sleep quality, and metabolic risk115. Personalized strategies based on chronotype can yield more effective health outcomes.

Larks: Eat breakfast soon after waking, finish dinner early.

Owls: Delay breakfast until hungry, but avoid eating too late at night.

Genetic Variability

Genetic variants in circadian-related genes can influence individual responses to diet and meal timing, highlighting the need for personalized nutrition strategies1020.

The Role of Technology

Wearable devices, continuous glucose monitors, and AI-powered apps can help individuals track how meal timing affects their unique biology, allowing for more precise and effective interventions20.

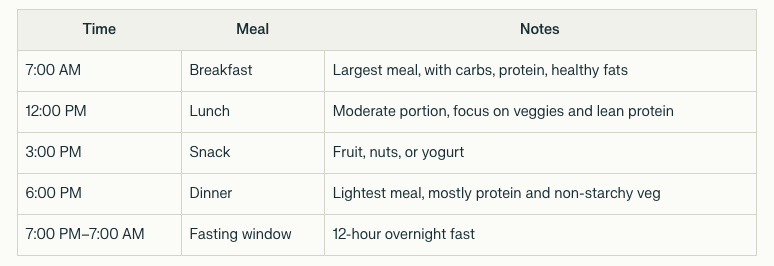

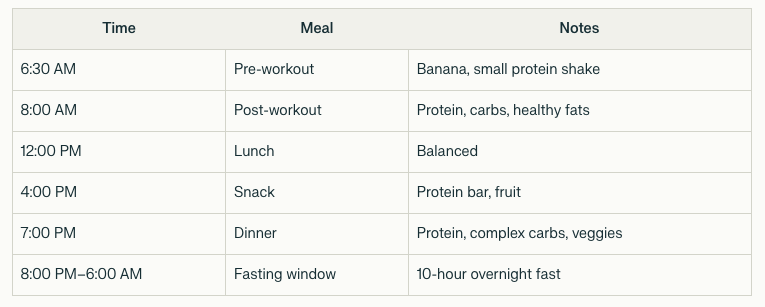

Practical Meal Timing Templates

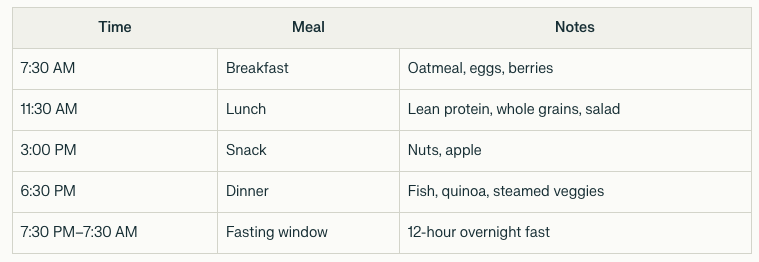

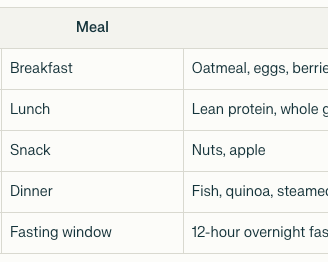

For Weight Management

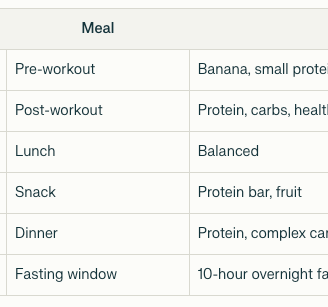

For Athletes

For Cognitive Performance

Chrononutrition and Disease Prevention

Diabetes

Aligning meals with circadian rhythms improves blood sugar control and reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes. Early TRE lowers fasting glucose and insulin levels in prediabetic adults2812.

Cardiovascular Disease

Irregular eating patterns and late-night meals are linked to higher cholesterol, blood pressure, and inflammation—key risk factors for heart disease2612.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

TRE and intermittent fasting are particularly effective for managing NAFLD due to their impact on body weight and fat loss2412.

Cancer

Chronodisruption may increase cancer risk by impairing DNA repair and promoting inflammation. Consistent meal timing and overnight fasting support cellular repair and reduce cancer risk420.

Chrononutrition and Sleep Quality

Meal timing also affects sleep. Later meal timings, including late dinners and frequent meals, are associated with poorer sleep quality and irregular sleep/wake cycles16. Regular breakfast consumption and early dinners improve sleep quality and support a healthy circadian rhythm1620.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

Myth 1: “Breakfast is Optional”

Regular breakfast eaters have better weight control, improved insulin sensitivity, and lower risk of heart disease817.Myth 2: “You Must Fast for 16+ Hours”

Even a 12-hour overnight fast provides significant metabolic benefits, especially for beginners411.Myth 3: “Calories Are All That Matter”

Timing matters: Eating the same calories late at night leads to more weight gain and metabolic issues than eating earlier813.Myth 4: “Late-Night Protein Builds More Muscle”

Late-night protein is less efficiently used for muscle synthesis and more likely to be stored as fat, especially if daily protein needs are already met5.

Adapting Chrononutrition to Busy Lives

For Shift Workers and Travelers

Anchor meals to your wake cycle, even if it’s nighttime6.

Use light exposure to reset your internal clock.

Fast during flights to help your body adjust to new time zones.

For Busy Professionals

Batch-prep meals and snacks to avoid skipping meals.

Set reminders for meal breaks.

Choose portable, healthy snacks to maintain regular eating patterns.

The Future of Chrononutrition

Personalized, Data-Driven Approaches

Advances in wearable technology, AI, and continuous glucose monitoring are making it possible to personalize meal timing based on your unique biology1020. Expect to see chrono-nutrition become a cornerstone of preventive medicine and chronic disease management.

Chrononutrition Across the Lifespan

Emerging research is exploring the role of meal timing in maternal and infant health, childhood development, and healthy aging, with the goal of optimizing health outcomes across generations11519.

Conclusion: Harnessing the Power of Meal Timing

Chrononutrition is more than a trend—it’s a science-backed approach to eating that aligns with your body’s natural rhythms. By timing your meals to support your circadian clock, you can optimize hormone balance, metabolism, and overall health.

Key Takeaways:

Eat with the sun: Prioritize larger meals earlier in the day, and avoid heavy late-night eating.

Fast overnight: Aim for a 12-hour fasting window to support fat burning and cellular repair.

Stay consistent: Regular meal times help maintain hormonal balance and energy.

Adapt to your lifestyle: Even small changes in meal timing can yield big results.

Whether your goal is weight loss, peak athletic performance, sharper thinking, or simply feeling your best, the timing of your meals matters. Embrace chrono-nutrition, and let your body’s natural clock guide you toward a healthier, more vibrant life.

References are available upon request and include peer-reviewed scientific journals and clinical studies supporting the benefits and mechanisms of chrono-nutrition as detailed throughout this article.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1516940/full

https://www.ifm.org/articles/chrononutrition-food-timing-circadian-fasting

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jnsv/68/Supplement/68_S2/_article

https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2024/april/is-it-time-to-consider-chrono-nutrition-in-general

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2020.00018/full

https://consensus.app/questions/principles-chrononutrition-applied-optimize-meal-timing/

https://repository.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4840&context=gradschool_theses

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0308172

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.11.13.23298454v1.full-text

Nel Wellness

Explore our range of health and wellness products.

Contact

nelwellness@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.